|

||

|

|

||

|

Home |

General Information |

Gallery &

Reference |

History

|

News

& Events |

Community

|

Contact Us |

||

|

|

| Crescent History | Bath History | Literary Bath | Bath at War| What If? |

| Royal

Crescent History

Click on the following bookmarks to read the history of:

Residential Bath in the Nineteenth Century By Leslie Jenkins "It's actually eighteenth century speculative building". The casual visitor to No. 1, Royal Crescent, the Georgian house in Bath furnished in contemporary style, now a museum run by the Bath Preservation Trust, is usually astounded at this information about Royal Crescent, John Wood the Younger's acknowledged masterpiece. A further shock registers if told how Jane Austen heartily disliked Bath. Indeed many visitors arrive with preconceived ideas about this European Heritage city, often based on literary references in writers as diverse as Fielding, Smollett, Sheridan and Charles Dickens. Mr. Pickwick, on visiting the Assembly Rooms accompanied by the M.C. Mr. Bantam, was admonished that in Bath ladies were neither old nor fat. Modern visitors should judge for themselves! The two Woods, father and son, constructed houses purpose built for accommodating families who came down to Bath from London for the "season". Local owners, such as Dr. William Oliver, of Mineral Water Hospital and Bath Oliver fame, let out their properties without actually living there themselves. Such a Georgian house was often one room wide and two rooms deep, dining room and parlour: on ground level, drawing room and second parlour on first floor, bedrooms on second floor, with servants' quarters in the attic. Below street level the kitchen and cellars reposed in the basement, steps from the street leading to the "Area", by which the servants entered. When Mr. Pickwick's servant Sam Weller has a letter delivered to his master's lodgings in Royal Crescent, the messenger is instructed to ring the "airy bell", as he certainly would not he welcomed at the front door. Popular belief is that Bath declined in status from the early nineteenth century onwards, beginning with the Prince Regent's popularisation of Brighton. Dickens is commonly thought to have hinted at such a decline in his account of Mr. Pickwick's visit to Bath in the 1830s, though this is not really evidenced in the text. True, Mr. Pickwick, Sam Weller, and the Dowlers take lodgings on the upper floors of a house in Royal Crescent, complete with a landlady Mrs. Craddock. However, the Crescent is suitably outraged when the hapless Mr. Winkle is trapped outside in a flapping dressing gown after one of those famous front doors slams upon him. What was the actuality? The Census returns for Bath from 1841 to 1891 would appear to supply an interesting answer. Taking Brock Street as an instance of residential Bath, and looking at one house in particular, one can form some conclusions. The street itself, built by the younger John Wood in 1767, links Royal Crescent with the Circus, the Gravel Walk once the sedan chair route from the Crescent to the city skirting the gardens of the houses on the southern side. The cosmopolitan nature of the residents is immediately evident. From 1841 through to 1891, all parts of the country are represented, certainly not only London. The Empire gives back retired tea planters, Her Majesty's Army and Navy are to the fore, Dublin is clearly still part of the "United Kingdom", there is a Swiss lady's maid and a domestic servant born in South Africa but a "British subject". Absentee clerics include a Dean of Salisbury and Aaron Foster, vicar of Mudford, near Yeovil, in 1851. Quite the most staggering feature of the Census returns throughout this period is the proportion of males to females, the women outnumbering the men not just two to one but more often five to one five men to twenty five women on a typical .enumerator's sheet. Highly literate enumerators, too impeccable handwriting, with the occasional pedantic insertion. Careful differentiation in servants' status: butler, footman, lady's maid, parlour maid, kitchen maid, cook. How very different from many Somerset village returns for the same period, when few inhabitants had been born more than a mile or so from their current home, where male and female numbers were more or less equal, with the vicar often the only person from further a field, Bristol deserving that distinction. Narrowing the vision from street to one house, at No. 16 every Census return shows a change of occupants. Notably, the inhabitants are of independent means e.g. Elizabeth Hopkins, in 1851, fund holder, aged 72, of London; Catherine Harrison, in 1881, income from lands, houses and dividends, aged 73, from nearby Frome; Anne Pritchett, also in 1881, living on dividends from the Planet Investment Society, aged 17, from Oxfordshire. Most intriguing of all, in 1861 the head of the household is George Mason, aged 56, a clergyman without care of souls", from Bradford, Yorkshire, married to 33 year old Helen Mason, of London Middlesex". Would Catherine Harrison, one wonders, have agreed with Oscar Wilde's Lady Bracknell that land "gives one position but prevents one from keeping it up"? All the others preferred investments and would doubtless have received the formidable dowager's approval. Each return shows a substantial proportion of servants to residents. In 1841 two servants looked after just three inhabitants; in 1881 four servants ministered yet again to three people. Domestic service appeared to attract country girls from the surrounding counties of Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Dorset, fewer servants coming from the city of Bath itself. In 1861 the Reverend George Mason brought butler and lady's maid from his native Yorkshire. Similarly, in 1881 Emma, Pritchett, from Oxfordshire, Newland Coggs, brought a housemaid from Eynsham, in the same county. Only at one time during the period does the house appear to have been divided rather than being occupied as the one unit for which John Wood had originally designed it. Two families, the Harrisons and the Pritchetts, shared the house in 1881. As only one cook, Anna Knott, is listed in the 1881 Census, she may perhaps have cooked for both families, especially if they were related, the kitchen being in the basement, with a central staircase giving access to all floors. Unlike Mr. Pickwick's house in the adjacent Royal Crescent (even the prestigious No. 1 in 1891), No. 16 does not appear to have been used as a rooming or lodging house. Apart from 1891, when Leicester Selby, a "Clerk in Holy Orders", aged 44, from Smethwick, is described as a "boarder", the 1841 1891 Census returns indicate that No. 16 never had more than seven inhabitants and never less than two servants. Contrary to popular belief, there were lodging houses on the southern side of the street, overlooking the Gravel Walk and Royal Victoria Park. The northern side what Lady Bracknell would have termed the "unfashionable side" with its less attractive view across the street is commonly thought to have produced the lodging houses. Not infrequent is a lodging house where the wife is the proprietress and the husband engaged in a lucrative trade such as furniture dealing. Amongst the guests in such houses are music and dancing teachers. What, then, are the conclusions? Dickens noted the "queer old ladies and decrepit old gentlemen" round the card tables and in the tea room of the nearby Assembly Rooms, all dispensing scandal and gossip. Brock Street no doubt contributed during the century. However, much of the evidence suggests that it was not such a bad life. The house owners appeared to be comfortably off, the servants' quarters at the top of tile house at least enjoyed superb views over the Gravel Walk towards the Mendips. Perhaps the final word should be left with Dickens, who summed up the typical Bat day; “A very pleasant routine, with perhaps a tinge of sameness.” The Royal Crescent in the Nineteenth Century By Monica E Baly In the last issue Leslie Jenkins gave us an interesting picture of Brook Street in the C1`9th. Analysis of the Royal Crescent gives a similar picture only, of course, the Crescent was rather more tip market in property values. Until the census returns of 1841 we cannot he precise about who lived in each house in the Crescent expect where we have literary evidence, for example the Linleys, Ansteys and the Thicknesses. In most cases the owner did not live in the house but leased it to tenants who generally paid the poor rate and it is from the rate book that we build up our picture. But tenants came and went, and irritating to the historian, changed houses and numbers at will. The early ratepayers appear a prestigious group and included Lady Malpas (20) Lord Demontall (17), Lady Stephey (21) the Hon. John Lewis, Dean of Ossory (22), Lady Elizabeth Stanley (24) Lady Mary Stanley (27) the Hon. Charles Hamilton (14) and [lie Duke of York at (15) and a number of others who sound like the persona in a Sheridan play. After 1841, however, with the census return it is possible to build a more accurate picture though we must remember that the enumerator's returns merely show the household on one particular night of [lie year. The returns 1841 1891 show a similar pattern to that found in Brock Street area are an unwitting testimony to the life of the upper classes in C19th Bath. Bath had become a Mecca for wealthy widows and spinsters. In 1871, out of the 30 houses no less than 15 were headed by a woman whose 'occupation' was usually listed as 'Fundholder', 'Landowner' or 'Independent'. For Bath, as a whole, women over 60 years were the largest group. (1) This is at a time when in England as a whole the largest demographic group was below 20 years and the age of expectancy between 20 and 45 years depending on your social class and locality. (2) Apart from elderly women the 'Heads' in the Crescent are now, not the minor aristocracy, but the burgeoning middle class described by R.S. Neale as 'the socially mobile, agrarian, capitalist Mile'. A number arc still listed as ,Fundholders' or 'Independent' but now occupations include Army Officer, Naval Captain (k., 11; 1 Y!), Bengal Civil Servant, Physician and Magistrate. This is Bath, having declined as a fashionable Spa, now attracting the more sober minded Society depicted by Jane Austen. As in Brock Street the birth place of the house holders is invariably outside Bath, often in the midlands and the north (where they probably had made their money). The servants on the other hand nearly all come from Somerset or Gloucester. As the century progresses the number of servants seem to rise, a concomitant of growing affluence during the industrial revolution and incidentally, a factor in the first wave of the emancipation of women movement. This house, No: 19, has a fairly typical living pattern for the period. Originally owned by John Jefferys, John Wood's financial advisor and the Town Clerk (did he keep the two functions separate?) in 1805 was sold to Elizabeth Walmesley and stayed in the Walmesley family until the end of the century but was let to tenants on long leases. Less than half the houses in the Crescent seem to have been owner occupied. 'A property owning democracy' was not a Victorian value. In 1841 the house was occupied by William Foskett of 'Independent' means aged 75, his wife Charlotte and an unmarried daughter, also Charlotte, aged 35 and with four young living in servants. Ten years later William had died and the head was now Charlotte aged 75, her daughter still unmarried and five living in servants. By 1861, mother has died and Charlotte is now head and listed as a 'Landowner' living here (on the night of the census) with her cousin Edward Wayne, a Cambridge undergraduate and four living in servants. Like Catherine Harrison in Brock Street (see issue 28) Charlotte would not have agreed with Lady Bracknell that 'land gives one position but prevents one from keeping it up!’ By 1880 one assumes that Charlotte had died and the ratepayer is Ann Phipps 'wife of an officer' with three small children and a cousin, Miss C.C. Wayne. This looks as if the tenancy had passed within the family and that the servants have been handed on, because the cook and the house keeper are the same and the housemaid, Emma Hales, has become 'nurse' but there are now a total of eight living in servants. This of course does not include people like gardeners, who presumably lived out. In 1891 the head of the house was the Reverend Edward Hanley, aged 48, the Rector of Northorpe, who lived here with his wife and nine servants including two lady's maids, a butler and a footman. One can only assume that Edward had inherited wealth for even by Victorian and Trollope standards nine servants (living in) for two people in a townhouse seems a little excessive. Looking at the Crescent as a whole between 1841 and 91 households show a similar pattern. 1 like No: 10 where in 1871 the head was Anthony Hamond aged 47 years who lived there with three young nieces and seven servants. He is still living there in 1891, now a J.P. but married with a wife aged 43 years. The nieces have left and there are not only five servants one wonders what happened to the nieces, did they marry, or did [lie new Mrs Hamond put tier foot down? At the other end of the Crescent poor Frances Silver, a widow at 39 years with seven young children had six servants including a governess and tier neighbour. Fanny Hawkins, a widow aged 49 with four children between the ages of four and fifteen had four servants. The Crescent was by no means childless. Behind the enumerator's fading, copperplate writing there must lay many untold stories. When they were not organising the servants how did all these women occupy their time? Were they engaged in [lie many charity organisations in which Bath abounded? Were they conscious of the poverty around Avon Street? Were they shocked that in 1841 Bath returned to Parliament what the Bath Chronicle described as: "Two disciples of revolution ..... Hot bed of all that is wild, reckless and revolutionary in policies" The two revolutionaries were of course J.R. Roebuck and Major General Palmer, both radicals. Contrary to what we think the Crescent must have been a hive of activity in the C19th. In 1871 there was something like 150 living in servants (see issue summer 1993, page 8). Did these servants know one another? Was there a coterie of butlers? Did the nursemaids meet and gossip on the sacred lawn? Were there ever romances between the servants? The unhappy Plight of the servants seems to be a constant concern to visitors to No: 1 but this is what EP Thompson calls 'the enormous condescension of posterity. (3) At a time when nearly a third of the citizens of Bath were receiving help from the Poor, Rate, getting into good domestic service was considered a reasonable aspiration. Servants in the Crescent were housed and fed and we know from the 1780 inventory at No: 14 that there, at least, the. Garrets were well furnished with carpets, curtains, mirrors, cupboards and goose feather beds and there was a special 'Necessary' in the garden which is something they would not have had in rural Somerset! Something else they would not have had in the country was medical attention; we know from the hospital records that employers being subscribers were able to get medical care for their servants and we know from the admission books that servants did indeed receive care, though how much good it did is a moot point. As I sit here in what was, presumably the house keepers, Jane Whatley's sitting room for 30 years and admire the view, I reflect that perhaps life for the servant class in the Crescent was not too bad. 1 feels sure Jane had an open fire. (1) R.S. Neal "Bath A Social 1 History 1680 1850" Routledge. (2) Edwin Chadwick 1842 "The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain", reprinted Longman 1965. (3) E.P. Thompson 1963 Making of the Working Class", Pelican Books Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History By Dr Monica E. Baly The Victorians' values and their way of life in the Crescent with servants, including coachmen and grooms, can be reconstructed from the extensive archive material available. While we are used to attempts by film companies to recapture life in late eighteenth century in Bath, little attention is given to life in the mid nineteenth century. But because of the availability of census returns and other archive material, it is easier to reconstruct the life of that period, and visualise who lived here before us. The original contract for the house and stables of No 19 was between John Wood and John Jefferys, gentleman, in 1771. John Jefferys appears to have paid the rates until 1803, but because there was no census return, we know nothing about his household. In 1804, the property appears to have been sold to Elizabeth Walmesley who paid the rates. I make this deduction because in 1840, when the rate book gives us both the name of the rate payer and the owners, she is listed as both. The Walmesley family appears to have owned the house until nearly the end of the century. Elizabeth ceased paying rates in 1840, so she probably died. In 1841, we have a census return. No 19 and the coach house were occupied by William Foskett, aged 75 years and 'of independent means', his wife Charlotte, aged 60, and his unmarried daughter Charlotte, aged 35 years. Also living in the house were four young servants. By the census return of 1851, William seems to have died and his wife Charlotte, now aged 75 years (sic) is the 'head of the house', which she occupies with her unmarried daughter and five servants: a housekeeper, a cook, a lady's maid, a butler and a housemaid. These are living in servants, but the garden is quite large, so there was surely a part-time gardener and probably a groom who lived out. The census of 1841 gives one third of Bath's working population as being engaged in domestic service. By the return of 1861, it seems that Mrs Foskett has died and the daughter Charlotte is now 'head' and listed as a 'landowner' and is then living with a cousin, Edward Wayne, an undergraduate from Cambridge, who is presumably away much of the time; again, five living in servants are listed. Ten years later, Charlotte, now 69 years old, is living alone with four servants. The butler has gone, but the faithful housekeeper and cook, who have lived in the house since 1851, remain together with two new maids. In 1880 Charlotte, then aged 75 years, must have died because the ratepayer becomes Ann Phipps, who appears on the census form of 1881 listed as 'the wife of an officer' and living with her three children under the age of 9 years and an unmarried cousin, Miss S. C. Wayne. Is this the sister of Edward, who stayed there 20 years before? This is interesting because the Fosketts were not the owners of the house, but the lease seems to have stayed within the family and with it some of the servants who have become family retainers. The cook and the housekeeper are the same and the housemaid, Emma Hales, now becomes the nurse, presumably for the children. But the interesting thing about this return is that for two adults and three small children there are now eight living in servants: housekeeper, cook, lady's maid, nurse, three housemaids and a butler; again, there were probably other part time employees such as a gardener. We have not got the census returns for 1891 yet, but the Phipps family seems to have gone by 1889. As I write in what John Wood called 'the garret', in what was probably the housekeeper Mrs Whatley's room, who, like me, lived in it for thirty years, I ponder what life was like then. Where did they all sleep? Was the front room in 'the garret' a dormitory for the housemaids and the nurse? Did the butler sleep in the basement? Did some sleep in the coach house? Where was the nursery? Who taught the children? Was Miss Wayne, aged 49 years, a poor relation who, rather like a Trollope character, helped with the children? And what became of her? What did eight servants do all day? Did the nurse maid take the children on the Crescent lawn and meet other nursemaids? If the census returns so far studied are anything to go by, there must have been some hundred to one hundred and fifty servants living in the Crescent. Did they know one another? Looking back over the long tenancy of Charlotte Foskett for forty years, one wonders what her life was like. In 1841, did she read aloud to Papa in the morning room? Was she content, or frustrated? Why did she remain unmarried? When she was the head of the house, what did she do in Bath? Was she engaged in charitable work, or did she have political leanings? Did she know her neighbours, and to what extent was the Crescent a community? The census returns are a splendid, unwitting testimony to the social and economic life of the nineteenth century. As the century advances and affluence increases so do the number of servants. While the owners and ratepayers generally come from other parts of the country, the servants are mainly drawn from Somerset and Gloucester, and one wonders if, when they had a day off, they were able to get home. Another surprising feature is the large numbers of widows and unmarried women listed as 'head' of the household, highlighting the difference in the age of expectancy, the death rates higher for boys than girls, and the high emigration rates and the demands from the services for men. No 19 for a long time seems to have been occupied by what we would can &a nuclear family', but other returns tell a different story and show that the extended family was common. In 1861, in No 15, there were two sons-in law, two daughters in law and a visitor living with Sarah Drinkwater, aged 75 and described as a 'Fund holder' from Ireland. There were also five living in servants. While, for all we know, the extended family may have been temporary, it is perhaps as well that there was no poll tax in 1861. My thanks to David Kirk for first sending me the census returns for No 19. Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

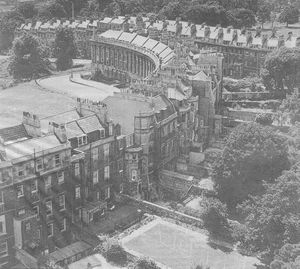

Dr Monica Baly recalls the time when Hitler tried to destroy The Royal Crescent At the outbreak of the Second World War Bath was considered to be safe from attack and received evacuees from London, and, at two days notice, the Admiralty, who requisitioned the hotels in the middle of Bath. After Dunkirk a bomber offensive was the main contribution that Britain could make to the war. At first it was anticipated that only military targets would be attacked, but after 1941 such niceties were no longer observed by either side. On 28th March, 1942 Bomber Command attacked the port of Lubeck which was also a mediaeval, Hanseatic town with wooden houses, of which 40 per cent were destroyed. Hitler was furious and vowed revenge. Part of the revenge was to be Bath. On 25th April, at 10.15pm 163 German bombers crossed the coast and as they turned towards Bath the sirens sounded but few people took any notice thinking that it was just another raid on Bristol. However, the actual sound of bombs falling galvanised people into action and most took cover, often in the large cellars under the road. The Kingsmead area suffered most and the whole area was soon alight with incendiaries on the way to the gasworks. The Civil Defence and Fire Services came into action but they were hampered because the telephones had been cut and there was no co ordination with the headquarters at Apsley House and there was a shortage of water. The incendiary bombs were effective in burning houses and creating a target for the succeeding aircraft but at first there were comparatively few casualties. The All Clear siren sounded and people came out of their shelters but soon the sirens sounded again and the wardens shepherded them back. One outstanding tragedy was the Scala cinema shelter in Oldfield which filled again and received a direct hit at one end. It is not known how many people in the shelter were killed, bodies were blown across the road and some were unidentifiable. At the same time bombs fell all around Oldfield Park and many houses were destroyed. People could see the bombers clearly and the gunning was so close that people had to take cover. First Aid workers and rescue services worked valiantly and ambulances took the worst casualties W the two hospitals where the staff worked continuously dealing with priority cases as best they could. The dead were left or ferried to make shift mortuaries. At last dawn appeared and the bombers flew off. On Sunday, 26th April with fires still burning and people digging in the rubble, the Salvation Army and other voluntary services trying to deal with the homeless and the bereaved, many people, fearing another attack, decided to get out of Bath even if it meant a night in the open. The impact of the incendiaries on No 17 This meant that some buildings were without firewatchers and some of the voluntary services were depleted. That night the sirens sounded again; this time the defending fighters had some success, but it was a harrowing night and several acres of buildings came under concentrated attack. Once again Kingsmead was the main target, a bomb fell on the rails at Bath Station and St John's House was demolished. Then the raiders attacked to the North. The most famous loss was the Assembly Rooms which had been newly restored. The Fire Brigade headquarters at No 3 Royal Crescent ceased to function when a near miss blew out the black out curtains; Nos 2 and 17 were gutted by incendiaries.

a view from behind theCrescent showing the impact on number 17 Behind the Crescent, on the triangle, St Andrew's Church went up in flames and much of Julian Road and around was devastated. That night two hotels were hit and partly demolished, the Francis in Queen's Square and the Regina opposite the Assembly Rooms, causing much loss of life. St James's Church, which stood on Littlewoods site, received a direct hit. Ironically, the crypt was being used as a mortuary for bodies from the previous night, now they floated out in the water from the Fire Service; one of the more macabre scenes of that dreadful night. Severe though the raids were they failed in the primary objective of destroying the cultural targets in Bath; the damage was mainly in the suburbs and the Georgian heart of the city was left largely untouched. But the damage was great. Three hundred and twenty nine houses were totally destroyed, 132 had to be demolished and 19,147 suffered some damage and the final death toll was estimated at over 400. Sadly, some bodies were unidentified and others were unidentifiable. Most of the bombed areas remained derelict for years. In 1958 the view from the back of the Crescent was of large areas of waste ground with a profusion of rose willow and buddleia and plenty of scope, amid the brambles, for the parking of cars. For years there was rubble at the end of Northampton Street and where St Andrew's Church once stood eventually, and mercifully, there was a green sward. On the North side, packing concrete blocks were erected on the rubble, named aptly Phoenix House, but they were sadly out of scale with the surrounding architecture and at odds with the typical Bath roof line. In the Crescent itself Nos 2 and 17 were sympathetically restored by the late Hugh Roberts of Brock Street, but for many years a number of the houses showed the signs of the ravages of war and neglect.

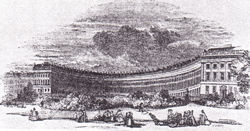

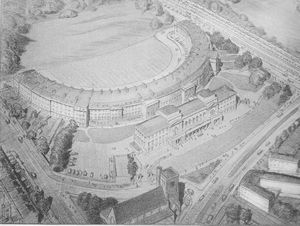

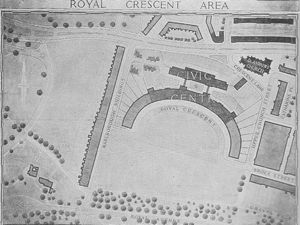

A close up of the new Council Chamber planned for the rear of the Crescent, separated by a forecourt from Julian Road. St.Andrews Church, bottom left, was to remain, with its spire removed. The Abercrombie Report of 1946, the plan for post war Bath envisaged massive rebuilding which would have destroyed much of the south of Bath and would have turned the Royal Crescent into Council offices surrounded by car parks (see map). The earth over John Wood the Younger's grave must have trembled. Fortunately the plan was too big to be adopted. As it was most of the architectural gems were rebuilt as they had been as was the case of the Assembly Rooms.

In many cases it was a question of infilling but in some cases valuable sites were lost. A wing of Green Park disappeared, St James's Church was pulled down as were other churches and chapels. In Carlton Road Georgian artisan cottages were replaced by what Fergusson calls 'hen coops' visible from every vantage point and the unloved Technical College, in the midst of Georgian houses, continued the isolation of the south west of Bath. At the back of the Crescent the complex of Georgian artisan houses around Lampard Buildings was lost. The Bus Station and the Southgate shopping complex, not exactly architectural gems, have replaced what was admittedly a run down area by the river. At the end of the war the residents of Queen's Square gave their garden as a memorial to those killed in the raids on Bath, but strangely there exists no official memorial to this tragic time in the history of Bath. Now fifty years on as we look at the phoenix that arose from the ashes we may ask with Adam Fergusson* which was the Sack of Bath, Hitler or the post war planners? 3 *The Sack of Bath by Adam Fergusson (Compton Russell, 1973). This article was taken from a lecture given by Niall Rothnie and his well researched book The Bombing of Bath (Ashgrove Press 1983), which can be read at the Bath Reference Library. Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History The Royal Crescent circa Thirty Years Ago By Monica E Baly 'Remind me to remind you we said we would never look back A reply to Mr Tom Rowland (Newsletter No 33 P15) The grass may have been growing between the setts and the lawn railings were in a poor state but, 'all but six of its houses divided into flats of varying grottiness' 'it was not'. Over one third of the houses had only one family or occupant, the rest, as now, were divided into either maisonettes or flats with varying degrees of skill, planning permission about alteration to the interiors was less strict that it is now. In total there were fewer housing 'units'. Nos 27 and 28, the home of Mrs Spenlove Brown were joined, as were numbers 13 and 14, as they are now. No 16 was a discreet Guest House and numbers 30 and 29 belonged to the West Dean estate where they housed 'the odd Cezanne or Van Gogh' for the owner, a son of Edward VII (illegitimate) who apparently spent most of his time in Texas. However, the estate paid the lawn fund without prompting, while the caretaker cultivated the basement garden with the glorious wisteria as one of the joys of the Crescent. The residents in the rest of this 'crumbling edifice' included, until she died in 1962, Lady Celia Noble who was a doyen of the musical world with whom Queen Mary used to come to tea when she was staying at Badminton. Lady Noble was succeeded by Miss Wellesley Colley, a great niece of the Duke of Wellington, complete with her Rolls and chauffeur, and when it came to the argument about the colour of the front door, had more money for QCs than the Council. At No 15 there was Mrs Tizzard, another patron of the arts, who held soirees to whom well known musicians came and on whose comings and goings we humbler residents looked on with awe. At No 21, the sister in law of Harriet Cohen, had five grand pianos and with whom Yehudi Menuhin came to stay and to rehearse. In those days, during the Festival, you could hear the concert for the evening being rehearsed and floating down from the windows in the Crescent. It is my proud boast that, on going to get into my car early one morning, (no parking problems in those days) I found Mr Menuhin (looking over the railings at the peaceful scene) who talked to me about Bath as being 'one of the last civilised cities in England' 1 agreed, and my day had been made. Further along the Crescent, among other distinguished residents there was Mr Jeremy Fry, with whom Princess Margaret came to stay, and who, with his neighbour in No 9, Charles Ware, was one of the main benefactors in the restoration of the Theatre Royal. Although No 16 had become a 'Guest House' its clientele was distinguished. 1 remember Lady Warwick, who I used to meet as did most residents putting in our orders at Cater, Fort & Stoffell, the high-class grocers who had a branch in Margaret's Buildings where orders were delivered free and brought up the stairs. Also in the Buildings there was a first class butcher. a wonderful cobbler who undertook all kinds of repairs, and a good greengrocer who also delivered, with sundry other useful shops that came and went, Everyone met in Margaret's Buildings, it was virtually our community centre. Supermarket shopping may be more efficient, but not nearly such fun and they do not deliver. The so called grottinness had some advantages, I remember this time thirty years ago well. I had injured my back and was off work for a month and I used to take myself on to the Lawn with a sun bed and read and listen to the birds. Not a sound anywhere but for the thrushes and blackbirds and the occasional car and perhaps the greeting from another resident who had come to join me. Then, of course, we were not security conscious car doors were left open as were front doors of divided houses. When collecting for Poppy Day 1 just went in and up the stairs and knocked on each door. I cannot pass over Mr Rowland's comment about No 1 being a 'Common Lodging House'. This is rubbish. A Common Lodging House was defined by Section 9 of the Public Health Act 1936 and had to be registered with the Local Authority, of which the Rowden Houses were a typical example; they were the last resort for the homeless. Now, alas, they sleep in doorways, under arches or in the parks. No 1 was merely a rather run down house that was sub divided into bed sitting rooms whose tenants were mainly elderly ladies whose main delight seemed to feed the birds in the park. And on the subject of the debate on windows and cills, Mr Rowland should pay a visit to the excellent Building of Bath Museum and get his facts correct. Of course some aspects of the Crescent have improved. More houses have had their stone cleaned, most roofs are now in good condition, the lawn railings and gates have been restored, thanks to the Royal Crescent Society. We have encouraged basement gardens which now attract more admiration than the Ionic columns, though; curiously enough 30 to 40 years ago a number of beautiful rose trees seem to sprout up from the foundations. On the other hand, thanks to our popularity for tourists with their coaches and buses, the road is in a far worse state and the stone towards the west end has darkened perceptibly. Mr Rowland's point is the rise in the market value of the houses. Property has probably risen by a factor of 25 to 30, but then so has what would now be my salary if I were still employed, and many other things. But is this our yardstick? The value of the Crescent is its unique beauty and the community spirit of the people who live here. The quality of life has little bearing on the market price of your house or flat. 'Talk about the market and valuation And the cash that goes therewith But the grotty Crescent yesteryear Chuck it Rowland' Monica E Baly With thanks to Mrs Cotter and the Spenlove Browns for helping my memory *with apologies to Chesterton The posh customers are up in arms This extract is from "By the Waters of the Sul" by the Society's ex Chairman Edward Goring from his time as a colunmist at the Bath Chronicle) THIS is an epitaph for Messrs Cater, Stoffell and Fortt. Not for their smart supermarket in that modem building in High Street but for the last highclass 19th century grocery merchant in Bath. Their branch in Margaret's Buildings closes next week. And the high class customers are furious. They are organising a petition to demand a reprieve for the quaint little shop which has changed little over the years. It gleams with polished mahogany, engraved glass lettering, monumental brass scales. It is staffed by smiling, greying ladies who scurry up and down the long, narrow shop to bring Earl Grey tea from remote corners and scurry back again for the sugar. It is the sort of shop where there are chairs. And customers sit on them. A shop which still thrives on the carriage trade round the corner in Royal Crescent and the Circus. Irate customers have complained to head office. Marion Hyde Smith said, "I blew my top. 1 cannot believe the shop is not making a profit. People queue for 20 minutes on Saturday mornings and are glad to do so." Claude Stoffell's widow said, "I am terribly upset." Marjorie Gwynne Hughes is organising a petition which begins, 'Ye are horrified and dismayed. It is a great blow to feel we shall no longer have the help, guidance and good fellowship of Mr Davey and his friendly staff. We must urgently implore you. . . " It was not a Bathonian decision. Mr Cater the grocer, Mr Stoffell the wine merchant and Mr Font the restaurateur may have got together in the 1880s but the firm is now part of Victoria Wine which is part of Showerings which is part of Allied Breweries, whose chairman, Wilfred Crawt, sits in an office in Guildford. "These businesses are nice and quaint but it's no longer a viable proposition," he said. It wasn't possible to give counter service and a competitive pricing policy. He had thought of turning it into self service but there would not be sufficient "customer throughput." He added, "A petition will not change my mind. The branch is trading at a loss." The firm is spending £7,000 on a new greengrocery alongside its High Street shop. William Pullin, Cater's general manager, says, "I have devised all sorts of schemes to avoid closing the branch but the premises are not really suitable for a food store. Closure was recommended ten years ago." After a record Christmas the three full time and seven part timers were told this week it will close on January 15. Brian Davey, 62, who has been offered the new greengrocery, says, 'Ye still have a lot of nobility on our books. Customers come from as far away as Shepton Mallet. We pride ourselves on personal service and high quality. We stock 30 to 40 difference cheeses and such things as mussel soup, shark's fin and kangaroo tail." Winifred Head, an assistant for 26 years, said, "Customers are queueing up to tell us how sad they are. One of them said she was going to stage a demonstration outside." January, 1972. The petition won only a temporary reprieve. Head office closed the branch six months later. The bidding in Royal Crescent starts at £40,000 This extract is from "By the Waters of the Sul" by the Society's ex Chairman Edward Goring from his time as a colunmist at the Bath Chronicle) WHAT price Royal Crescent now? The last time the question popped up was two years ago, when a house in Bath's most famous setting was sold for around £20,000. That shook people who could remember the 1950s when houses in Royal Crescent were standing empty at £4,000. Even in 1964 you could pick up one for £7,500. So what are they worth now the great gazumping property boom has sent the prices of Bath's Georgian houses to heights which make local estate agents dizzy in disbelief? Bernard Thorpe, the smart London agents who moved into the city last year, are expecting to get more than £40,000 for their first really big property plum, No 9 Royal Crescent. It came on to the market yesterday. And their top drawer composure will betray no sign of surprise if it sells for nearer £50,000. They are inviting offers. They have already had one for £37,000. They're expecting many more. "We're advertising it nationally and abroad," said a spokesman today. "We want to sound out the market. There are plenty of people who can afford £50,000 for a house like this," It is the home of Mrs G. M. Thomasson, one of the grand school of Royal Crescent residents, whose bearing reflects the elegance and dignity of the house itself. Her next door neighbour at No 10 is Charles Ware, the property developer who commutes between London and Bath and is equally at home among the trustees of Bath Preservation Trust and the hippies of the Other Festival. "I have lived here for 11 years but 1 am leaving to join my family in Suffolk," she said. "My great hope is that whoever buys the house will keep it as a house and not turn it into flats. It is one of the last private houses in the Crescent." It has three reception rooms, seven bedrooms, four bathrooms, a staff flat and a lift. June, 1972. Charles Ware sold No 1 0 for £34, 000 and bought No 9 for £45, 000. In 2005 a house in Royal Crescent was for sale at £4 million. Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

St. James's Square…The building of Bath From Newsletter No 46, Winter 2001 The development of St. James's Square began in March 1790. Sir Peter Rivers Gay, Lord of the Manor of Walcot, who also owned other parts of the city with streets name after him, granted to Richard Hewlett and James Broom a ninety nine years' building lease of some land to the north of the Royal Crescent. This land consisted of orchards and gardens on a sloping site, which at the time were tenanted by various residents of the Crescent, among them Christopher Anstey He was the author of the New Bath Guide and the plaque on Number Five Royal Crescent says that he lived there. Anstey's annoyance at being given notice to quit was given expression thus: 'Ye men of Bath, who stately mansions rear, To wait for tenants from the Devil knows where, 'Would you pursue a plan that cannot fail? Erect a Madhouse, and enlarge your jail?' To which came the riposte: 'Whilst crowds arrive, Fast as our streets increase, And our Jail only proves an empty space, Whilst health and care here court the grave and gay, Madmen it and fools alone will keep away.' The lease was granted to Hewlett and Broom on condition that they agreed to lay out a sum of at £10,000 'in erecting buildings and finishing stone messuages', and they engaged John Palmer, architect of Lansdown Crescent and the interior of the Pump Room, to design the layout and elevations for a large residential square with four tributary streets. Building was begun as soon as the site could be cleared and most of the houses had been finished by 1794. By this date James Broom owned property in Marlborough Buildings, for at least part of which he was sub architect. Article reproduced from the Newsletter of the Marlborough Lane and Buildings Association, by kind permission of its Treasurer Adam Brunton.

Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

Beneath the Surface: Digging around the Crescent By Ewan Fletcher From Newsletter No 51, Winter 2002 It is quite understandable that you might want a little more information from Channel Four's Time Team. We did after all dig up large sections of your front and back lawns and generally churned up rather a lot of mud whilst we were there. Luckily amidst this dirt and chaos we made some interesting discoveries. Whilst I must leave some suspense for the programme I am more than happy to give you a brief summary. There were several reasons for Time Team to choose the lawn of the Royal Crescent and the triangle off Julian Road as archaeological targets that would have the potential to make an exciting programme. Initial interests arose after conversations with Rob Armour Chelu of the Bath Archaeological Trust, who has worked with us on many of our programmes.' He, along with his colleagues Peter Davenport and Marek Lewcun has been interested in the area's archaeology for several reasons. Firstly, the Julian Road triangle had been the site of St Andrew's Church prior to its destruction in the Blitz. When this was built in the nineteenth century the architect noted discovering several stone coffins and bones which were potentially Roman. It therefore seemed likely that there may have been a Roman cemetery lining Julian Road. Secondly, when the school across the road was built fifteen years ago, large quantities of finds typically associated with Roman religious sites were discovered. This suggested that there was potentially a small temple or mausoleum in the area. Thirdly, some of the Bath Archaeological Trust archaeologists felt that there was evidence for a Roman road running across the corner of the triangle, presumably under the Crescent, and down the lawn. One argument was that this was the missing link of the then highly important Fosse Way. Fourthly, vague parch marks on the Lawn potentially indicated the presence of subsurface structures. As the Lawn is known not to have been built on in recent history there was room to believe that these may have been the remains of Roman architecture. Additionally, it is not often that archaeologists receive the opportunity to excavate in a World Heritage Site. The exciting possibility of discovering what the clues were pointing to, especially within the beautiful surroundings of the Crescent and Park, made this an ideal project for the Time Team to undertake. Of course non-intrusive speculation can sometimes be right. But sometimes it can be wrong and unproven; especially when one has only three days for careful excavation. While not wishing to give too much away I can let you know that the archaeology was far from straightforward and provided a really exciting challenge, especially in the torrential rain that soaked us. And we were certainly in for some surprises. Luckily some of these were truly interesting, including walls, ditches, small finds and skeletons. Although we don’t know the transmission date yet, it will certainly be shown on a Sunday sometime between early January and March 2003, and I suspect closer to the end of that period.

Beneath the Surface: Channel Four's Time Team comes to Bath By Roy Maxwell From Newsletter No 50, Spring 2003 Strange scorch marks on the Lower Lawn have been taken to be indicative of a Roman building, and perhaps more interestingly, under the triangle of grass at the back of the Royal Crescent, sarcophagi were discovered some 130 years ago when Victorians built a church on the site. These were the locations for Time Team's visit to Bath. The Church having been destroyed by bombing during World War Two, and with permission for an archaeological dig to take place on both proposed sites, Time Team set out to look for further evidence of Roman occupation on what was then the west end of Roman Bath. The plan was to dig downwards directly above where the sarcophagi were believed to be, and to dig trenches across the areas of interest the Lower Lawn. Of course, little went to plan. The detailed Victorian drawing showing the location of the sarcophagi was in fact a drawing of the original church structure, and there had been later church building directly over the sarcophagi. The trench on the Lower Lawn did not reveal a Roman building, as had been hoped, but natural variations in the geophysical landscape. However, there was exciting evidence of possible Iron and Bronze age settlement. Initial disappointment led to further digging at the rear of the Crescent, revealing a wonderful section of Roman wall, probably part of a domestic building. Further trenches on the Lower Lawn revealed skeletons buried in coffins in non Christian alignment i.e. North to South as opposed to East to West, alongside what is believed to be a missing section of the important Roman road the Fosse Way. The upward direction of the road, passing under what appeared to be Number 12 the Royal Crescent, corresponded with the site of the Roman building discovered at the back of the Crescent, confirming the importance of both sites. How many Roman skeletons are waiting to be discovered under the Crescent? Whilst the Time Team didn't find what they came in search of, they arguably found something much more important, and demonstrated once again that Bath is justly a World Heritage Site. But what will archaeologists of the distant future discover at these same sites, and more importantly how will they interpret their findings? Will there be reconstructions of teenagers bringing their votive offerings of litter, beer cans and other substances to scatter before their shrine to the god of the Ha ha. Others in uniform will be shown taking away these same offerings the following morning, only for the same ritual to be repeated day after day. What sense will they make of it? What indeed.

Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

THE

STUDIO FLAT THAT WILL SET YOU BACK A COOL £395K This is Bath - 29 July 2006 (reproduced with full permissions) Say the phrase, studio flat, and the image of a home on Bath's Royal Crescent is unlikely to spring to mind. But that is exactly what is on offer through city estate agents Cobb Farr. For a cool £395,000,you could pick up this property on the right, described as a "stunning and elegant ground-floor apartment" - but which does have the advantage of a courtyard garden to the rear. However, for your money, you do not even get a separate bedroom. The description does not go so far as to call the property a studio flat, instead stating: "Accommodation comprises entrance hall, fully fitted kitchen, bathroom, grand reception room/bedroom." And the advert's picture quite clearly shows an ornate bed lined up behind the plush sofas, and next to a cosy dining area, in the grand room which measures 25ft 2in by 21ft 4in. But it does dip more than £120,000 below the average cost of a home on the world-famous street. In February the Crescent was revealed to be the 26th most expensive street in Bath, with an average property price of £518,244. This is mainly down to the fact many of the townhouses are now divided up into flats. However, an entire property could cost as much as £6m. Antonia Jenkins, a director of Cobb Farr, said: "You have never seen a studio like it. "The current owners refurbished it, and when they did the work, they discovered the original plasterwork of scenes from Ancient Greece. "If you are a businessman staying in the Royal Crescent on a weekly basis and have good money, as so many do, it's a worthwhile investment." Despite the lack of space, a couple currently live full-time in the studio.

Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

Bath Goes to Pop A house in the city's

prestigious Royal Crescent is on the market. It may be a Georgian

gem, says Sonia Purnell, but modern gadgets have put grandeur firmly

in its place Royal Crescent, Bath, is the finest example of perfectly preserved Palladian architecture, part of a masterpiece of urban and social planning. Arguably Britain's most impressive residential road, it is a 500ft elliptical terrace of 30 magnificent houses and Ionic columns, built in honey-coloured Bath stone by John Wood the Younger between 1767 and 1775.

Instead of the chalky blues, greens and reds redolent of an opulent Georgian interior, the visitor is assaulted by the tans, mustards, mushrooms and blacks of a contemporary show home. There are no mahogany card tables and ornate gilt mirrors: the owners instead have installed multi-room audio systems, a sleek minimalist kitchen and an array of uncompromising modern furniture. Where you might expect to see an old master hanging on the walls there is an inbuilt water tank filled with exotic fish.

Overall, the 28 rooms in the vast main house (there is also a coach house, staff flat and planning permission for a mews house) are an essay in 21st-century luxury, with barely a backward glance at the building's origins. It may not be to the taste of traditionalists - you could easily imagine Georgian Society purists spluttering with indignation - but will appeal to a wealthy buyer seeking the latest gadgetry combined with authentic grandeur.

"We expect the buyer to be either a pop star wanting somewhere out of London or someone in movies," says Michael Hughes of Pritchards (01225 466225), which has put the house on the market for £4 million. "It will be someone young, trendy and successful. This is a very exciting event for Bath and sets a new style for the city."

The house has a reassuring range of mod cons, such as monitored security and fire detection systems throughout, a multi-line telephone system, dedicated internet rooms, new satellite television systems and water-filtration and softening units. But there are also boys' toys, not least a Scalextric set on a large board that can be lowered electronically from the billiard-room ceiling. Grown-ups can enjoy a dedicated wine-tasting room - a space discovered by the owners only after they had moved in - complete with stone wine bins, customised floor lighting and plenty of shelf space for glasses.

Children have the run of two playrooms in which to indulge their fantasies - one on the ground floor leading to the garden, the other on the third floor next to their bedrooms. The latter, at the top of the house, has walls professionally painted with Wild West scenes of half-size cowboys, cacti, bison and horses. On the floor below, the master bedroom is fitted with plain, full-length burr sycamore panelled doors that hide a sensationally large television. Beyond the dressing room is the en-suite master bathroom, the nicest room in the house - kitted out by Philippe Starck - with stunning views of a gently sloping park and the centre of Bath beyond.

The owners have clearly spared no expense. Downstairs, the 25ft by 16ft kitchen has a Zimbabwean black granite worktop and a buffet unit finished with heat-resistant lacquer. Lighting in the room is controlled by a four-setting mood lighting system, and the hall and conservatory have Jerusalem old-gold limestone floors.

Below stairs, the cavernous basement gym is equipped with a silk-lined acoustic wall panel to reduce sound reverberation. It also hides the original kitchen cupboards, which the present owners ripped out but, because the house is Grade I-listed, were not allowed to throw away.

Today's No 25 is a far cry from the house sold three and a half years ago by an elderly couple who had lived there for years with their nurse and a nephew. They left behind a warren of neglected rooms, some without electricity and reliable hot water. The current owners, a professional couple with two young children, have worked on dragging it into the modern age ever since. Yet, just as they have completed what must have been a mammoth exercise, they want to sell up and find a plot of land elsewhere in Bath to build a new house.

Property prices have soared in Bath in recent years, doubling in the Royal Crescent in the past five years alone. A decade ago a whole house would have cost no more than £800,000. In the 1970s, when the Crescent fell into disrepair and the extremely grand No 1 was a scruffy b&b, they were priced at only £5,000.

It was not until Major Bernard Cayzer, a member of the shipping family, rescued No 1 from ignominy and gave it to the Bath Preservation Trust, which raised funds to restore it, that the Crescent began its climb back to respectability.

When it was built, it was one of the most fashionable addresses in the country, attracting among other distinguished and wealthy residents, the Duke of York, the second son of George III. Master craftsmen were recruited in droves to decorate the interiors to designs drawn from the many pattern books of the time.

Now its most distinguished resident is probably Andrew Brownsword, the former greetings card king who sold out to Hallmark in 1994 for £165 million. He owns two houses knocked together, complete with swimming pool and double-sized garden, and estimated to be worth £10 million.

As in London, Bath, which has some of Britain's most expensive property outside the capital, has seen its property market peak. Houses around the £1 million mark have fallen in value by 10 per cent since last summer. But Pritchards believes that the top end is still immune from the economic downturn. In the case of No 25 Royal Crescent, however, the unremitting contemporary look and bold colours may well narrow the market.

The owners have lavished money on restoring the house and the sale price is a record for Bath. There is still serious money around and the house has great rarity and prestige value. However, if the "trophy" end of the property market in London is anything to go by, this may not be an easy sale.

Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History THE ROYAL CRESCENT RAILINGS AND FOOTPATH Harrison Brookes Architects 2016

OBJECTIVE in order to repair the railings and coping stones to the crescent lawn it will be necessary to remove the existing tar macadam path surface. Prior to doing this the nature of the paths reinstatement needs to be considered. To inform any decision, the evolution of the path needs to be looked at to identify its date and its original form. As a by product of other research, Harrison Brookes Architect (HBA) have unearthed records from the Council Minute books held at Bath Record office, and photographs held in the Bath Reference Library, which may shed more light on the situation. This information is set out below.

MISCELLANEOUS 1) Public Health Act 1875 In 1875 the government brought in the public health act which was intended to improve the sanitary conditions in large urban centres. Initially it dealt with sewers but it quickly expanded to include drainage.

2) Rivers Pollution Act 1876 In 1876 the Rivers pollution act was commissioned which looked at the issue of groundwater runoff and industrial use of rivers in an attempt to control pollution and flooding. As part of this act came about the introduction of storm drains.

3) Flood prevention works. 1896 onwards The council minute books which date back to 1896 are littered with references to the issue of flooding in Bath and the need to control water from the streets. From the 1876 onwards a campaign of street drainage improvement had been identified as being important if flooding and public health was to be controlled.

4) Ordnance survey Map 1885 Map clearly shows the Royal Crescent without the presence of a footpath against the railings to the crescent lawn. The area occupied by the pavement shows lamp points. This map is the last map of a suitable scale which shows the Royal Crescent.

COUNCIL MINUTE BOOKS

5) Feb 1896 “A special meeting of your committee was held for the purpose of considering the question of the general condition of the pitching and paving of streets in the city and after full deliberation it was decides to ask the representatives of each ward upon this committee to inspect and report.”

6) 1st April 1896 item 9 “The question of removal of stone pitching form the roadway in front of the Royal Crescent and the substitution therefor [sic] of macadam has received the most careful consideration of the committee and having ascertained that the majority of the residents favor [sic] such a change the necessary expense of carrying out the work is also in included in the estimate.”

7) 24th June 1896 item 8 “The necessary temporary repair to pitching in the Royal Crescent have been carried out by your surveyor.”

8) 4th January 1897 p 27 item 9 “A memorial has been received from some of the inhabitants in the Royal Crescent, calling attention to the state of pitching there, and the consideration thereof has been deferred pending the laying of a trial length of tar macadam as soon as the conditions of weather permits.”

9) 15th April 1897 p109 Resolution; “That the roadway in the Royal Crescent be repaired with tar macadam at a cost of £405 instead of pitching estimated at £850"

10) 27th April 1897 p119 Resolution moved as an Amendment by Councilor Morris. “That the resolution as to the repairing of the roadway to the Royal Crescent be not carried out and that the original proposal to relay with pitching be reverted to.”

11) 10th May 1897 p 150 item 2 “The clerk reported the resolution of the Authority as to the Royal Crescent pitching. Resolved: That the surveyor be instructed to order necessary pennant pitching and report to the sub surveying committee as to the way in which he proposes to carryout the works - the subcommittee to inspect and report this fortnight”

12) 9th June 1897 p 180 item 3 “The report of the sub surveying committee contained the following recommendations was read and adopted, namely; That the consideration of the surveyors report on pitching Royal Crescent be adjourned.”

13) 21st June 1897 p 182 item 5 “The report of the sub surveying committee contained the following recommendations was read and adopted, namely; That the surveyor be instructed to order Caithness Stone for the Abbey Churchyard and Royal Crescent.”

14) 19th July 1897 p 221 item 6 “That the surveyor be instructed to proceed with the relaying of so much of the roadway in the Royal Crescent as he can obtain the necessary stone for in the present season.”

15) 25th October 1897 p297 “The report of the sub surveying committee containing the following recommendations was read, namely; That the sum of £125 should be paid to Mr J.W Welch on account of this contract for pitching and paving works at the Royal Crescent.”

HBA NOTE: The word “paving” is used for the first time. We take this to mean the footpath which forms part of the carriageway. Additional minutes relating to other payments exist subsequent to October 1897 however these provide little additional information.

16) 6th June 1898 p297 “Mr Councillor Young drew attention to the delay in completion of the pitching of the Royal Crescent and the Surveyor reported that he was unable to get pitching material delivered. Resolved: That the surveyor be instructed to complete the works in old materials.”

17) 1899 Surveying Committee minutes No mention of royal Crescent works. It is therefore assumed that the works were completed in the year 1898

18) 1899 - 1932 The records were searched for the next 30 years until 1927 with no further reference being made to the Royal Crescent. It is therefore assumed that the pavement was introduced in 1897 when the road was substantially rebuilt

PHOTOGRAPHS

19) Circa 1905 Paul De’Ath Collection One of the best images of the crescent railings is in the collection of Paul De’Ath which supposedly dates to 1905. This image shows the road without a footpath, but does show the gutter line and the full extent of coping stones. HBA have asked Paul De’Ath to confirm the dating of this image which is thought to be suspect. (this picture is not available at time of web publication).

20) Circa 1932 Peter Laws Collection “Bristol Bath and Wells Then and Now” shows an image of the Royal Crescent in 1932 taken by Peter Laws with a horse and carriage and early motor car. The image is dated 1932 and clearly shows the foot path in place.

21) 27th April 1942 RAF bomb damage photograph After the blitz of 1942 photographs were taken of the city. Copies of these are currently held in Bath Reference Library under Photos V20. One such photo shows the bomb damage to the Royal Crescent. It clearly shows no 2 and 19 Royal Crescent burnt out and a large crater in the road outside No 19. Debris can be seen extending beyond the railing line onto crescent lawn. 22) May 1942 Repair works to the bomb crater in the Royal Crescent were commenced in May 1942. A photograph was taken at this time which clearly shows the presence of the pathway against the railings. Interestingly it also shows material stacked up against the railings including paving slabs. It is possible that these were the early paving stones laid by Mr J.W. Welch. er 23) FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS Further detailed aerial photographs have been ordered to look in detail at the paving. In addition service plans have been ordered to determine if the original surface was removed as a result of the introduction of services such as telephone, water, electricity etc. Post card collections are to be consulted for additional information and the NMR has been asked to provide images taken in 1942 of the bomb damaged railings.

24) CONCLUSIONS It is clear from map evidence of 1885 that no path existed against the park side railings of the Royal Crescent prior to this time. Around this time the council minute books suggest that there was a city wide campaign of highway and drainage improvement, presumably in response to the various Act’s of parliament that came into force in the 1870's. As part of this campaign the road outside the Royal Crescent was identified as needing major repairs. There then seems to have been some debate as to the nature of the roads surface treatment. In the end, pitching (setts) seems to have won the day although it was twice as much as the option of tarmacadam. This was obviously carried out as payment was made to the contractor, however it seems to have taken over a year to do as there was a short fall of material.

Whilst no specific reference is made to the formation of a pavement in the records, payment was made to the contractor for “pitching and paving”. This coupled with the images of 1942 which tantalisingly suggest that paving stones were present in the immediate area in the early 1940's all point to the reasonable conclusion that the railing path was originally paved with stone.

There is some contradictory evidence as to the date of the path with a Paul De’ath image suggesting that in 1905 the pavement was not in place. However there are no council records from 1898 to 1932 indicating any work to the Royal Crescent road. Given the weight of evidence we believe that it is more likely that the image has been mis-dated rather than the records excluding what would have been a significant amount of work. Go to top of page / Return to Royal Crescent History

|

|

Copyright 2011 Opus 57 Ltd , All rights reserved Website developed and managed by Opus 57 Ltd |